The American road trip has been hijacked by efficiency. We calculate fuel stops with GPS precision, optimize routes for minimal time, and treat rest areas as necessary evils rather than portals of discovery. Yet the neuroscience of long-distance driving reveals a cruel paradox: the more we focus on reaching our destination, the less we remember of the journey. Research from transportation psychologists shows that drivers who vary their stops retain 40% more trip details than those who follow rigid patterns.

The infrastructure of monotony is deliberate. Interstate highways were designed for speed, not exploration. Exit ramps lead to predictable clusters of fast-food chains and gas stations, a commercial ecosystem engineered for familiarity. But just beyond that frictionless friction lies a parallel universe of fossil beds, soda fountains from the 1890s, abandoned Cold War missile silos, and pie shops where the recipe hasn’t changed since Eisenhower. Finding these places isn’t luck—it’s a learnable skill.

The Biology of Boredom: Why Your Brain Needs Strange Stops

Highway hypnosis isn’t a metaphor—it’s a measurable neurological state. At sustained speeds above 60 mph, your brain’s default mode network activates, creating a trance-like focus that conserves energy but filters out novelty. You’re physiologically incapable of noticing the hand-painted sign for fossil falls or the historical marker for a forgotten battle. This is why intentional stopping matters: you must break the trance before it breaks you.

The 90-Minute Reset

Transportation safety studies reveal that cognitive performance degrades significantly after 90 minutes of continuous highway driving. Reaction times slow, peripheral vision narrows, and risk assessment becomes impaired. The solution isn’t just rest—it’s **different** stimulation. A 15-minute stop at a bizarre roadside attraction activates different neural pathways, effectively rebooting your attention system.

Think of interesting stops not as delays but as neurological maintenance. That vintage soda fountain in Randsburg, California—where they still use phosphates to make lime sodas from 1898 recipes—does more than quench thirst. It forces your brain to process unfamiliar sensory input: the hiss of carbonation, the tartness of real citrus, the patina of a century-old marble counter. This novelty is what prevents the highway from becoming an unmarked stretch of forgotten time.

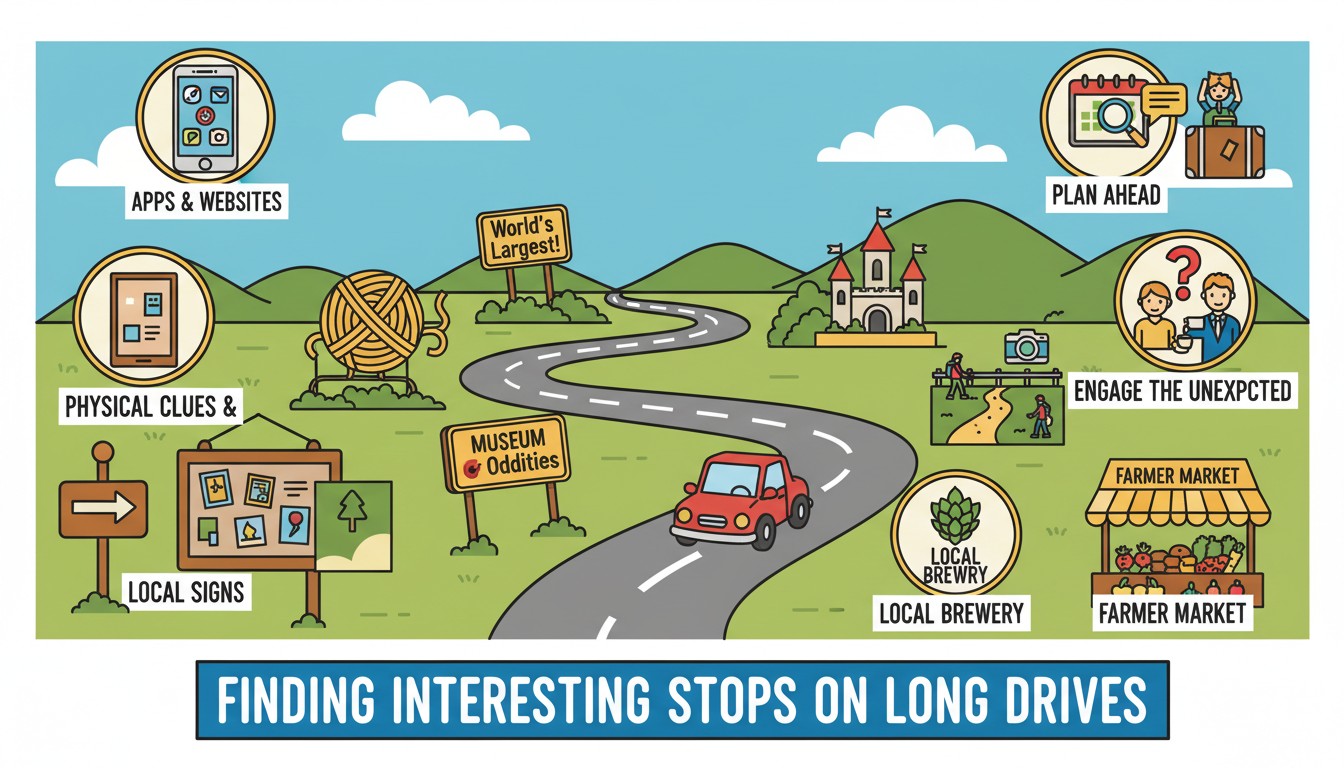

Digital Dowsing Rods: Using Technology to Find the Past

The paradox of modern travel is that our phones, often blamed for disconnecting us from place, can become powerful tools for discovering it—if used deliberately. The key is shifting from passive consumption to active, strategic searching.

Atlas Obscura and Roadside America: The Curiosity Catalogs

These two platforms function as crowd-sourced treasure maps. Atlas Obscura excels at the genuinely weird and historically significant—a Cold War missile silo turned museum in Kansas, a forest of bent trees in Poland, a chapel built from human bones. Roadside America specializes in the cheerfully kitschy: the hubcap capital of the world, a 25-foot-tall woman in Pearsonville, California, or a house shaped like a lemon.

The strategy, as seasoned road trippers demonstrate, is to plug your overnight stops into both platforms the night before. Create a custom Google Map layer with the attractions that intrigue you, color-coded by priority. Red for can’t-miss, yellow for maybe, green for “if we have time.” This transforms spontaneous discovery into a menu of possibilities you can consult when energy and curiosity align.

Google Maps: The Layered Approach

The world’s most powerful mapping tool is wasted if you only use it for turn-by-turn directions. The secret weapon is the “Explore” tab combined with saved lists. Before your trip, create a list called “Highway Possibilities.” As you research, save anything interesting—diners, viewpoints, historic markers, trailheads. When you’re on the road, open the map and see what’s nearby. The app shows you not just what you planned, but what you *might* want to plan.

Pro technique: zoom in on your route and search for terms like “vintage,” “antiques,” “museum,” “brewery,” or “historic.” The algorithm reveals layers of place that highway signage deliberately hides. That “antique mall” 3 miles off exit 142 might be a junky goldmine. The “historic site” marker could lead you to a preserved 1800s stagecoach station with a volunteer docent who tells stories that never made textbooks.

The Dyrt and Campendium: For the Overnight Adventurers

If your long drive includes camping, these apps reveal a parallel universe of overnight possibilities beyond RV parks. Free dispersed camping on BLM land, remote forest service sites, hot springs accessible only by dirt roads. A cross-country traveler documented using these apps to find camping spots first, then overlaying Roadside America to discover attractions near each overnight stop. This inverted planning—sleep first, explore second—creates a more relaxed rhythm that favors discovery over deadline.

Human Intelligence: The Lost Art of Asking

For all our digital wizardry, the most reliable source of interesting stops remains the same as it was in 1955: humans who know the territory. The key is asking the right humans the right questions.

The Locals’ Local: Where the Staff Eats

When you stop for gas, don’t ask the cashier “What’s good around here?”—ask “Where do you eat when you’re not working?” The first question triggers a tourist script; the second demands personal truth. The answer might be a taco truck in a grocery store parking lot, a family-run diner where English is a second language, or a barbecue joint that sells out by 2 PM.

The same principle applies at breweries, gear shops, and visitor centers. In Bishop, California, along Highway 395, the staff at Erick Schat’s Bakery—famous for sheepherder’s bread—will direct you to the Ancient Bristlecone Forest, where 4,000-year-old trees stand. They’ll tell you which hike has the best views and which is overrun. This information never makes it into apps because it’s too fluid, too locally specific.

The Biker Intelligence Network

Experienced long-haul bikers have mapped America’s back roads through decades of trial and error. As cross-country road trippers advise, “Ask older bikers where the prettiest local drives are.” This isn’t casual advice—it’s accessing a living database of scenic byways, hidden hot springs, and roads that are empty but spectacular. Bikers stop where the riding is good, not where the franchises cluster.

Pull into a roadside diner where a dozen Harleys are parked. Order coffee. Listen. You’ll hear about the waterfall 12 miles down a forest service road, the best time to see wildflowers on a particular pass, and which “scenic viewpoint” is actually a tourist trap. This intelligence is real-time, unfiltered, and validated by people who’ve ridden it.

Visitor Centers: The Underrated Goldmines

Modern visitor centers have evolved beyond brochure racks. Many now employ local history enthusiasts who can direct you to the living history you’re seeking. The key is engaging them beyond the obvious: “I’m interested in pre-WWII industrial sites” or “Where would I find the best example of Art Deco architecture within 30 miles?”

In Lone Pine, California, the film museum staff will tell you not just about the 300+ movies shot in the Alabama Hills, but which dirt roads lead to the exact locations where John Wayne stood. They’ll show you how to frame Mt. Whitney through Mobius Arch, a natural rock window that photographers prize. This is information that takes hours to find online, delivered in five minutes of conversation.

The Thematic Drive: Building Stops Around Obsessions

The most memorable long drives aren’t routes—they’re scavenger hunts. Choosing a theme transforms the highway from a conveyor belt into a treasure map. The theme could be culinary (every small-town bakery), historical (Civil War markers), architectural (Art Deco post offices), or absurd (world’s largest things).

The Food Trail: Beyond Fast Food

Instead of eating wherever you happen to be hungry, plan your fuel stops around specific food quests. Use local food resources: farmers markets, regional specialties, family-owned diners. A drive down Highway 395 becomes a moveable feast: antique sodas in Randsburg, sheepherder’s bread in Bishop, fish tacos at a Mobil station in Lee Vining (Whoa Nellie Deli, famous for its unlikely location and exceptional food).

The key is researching regional signatures. In Texas, it’s barbecue joints that run out of meat by mid-afternoon. In the South, it’s meat-and-threes where the vegetable sides are cooked with ham hocks. In New England, it’s clam shacks that close when they sell the day’s catch. These places don’t advertise on billboards; they survive on reputation and local loyalty.

The Industrial Archaeology Route

America’s highways follow the bones of industrial corridors: abandoned railroad lines, derelict factories, preserved charcoal kilns. The Cottonwood Charcoal Kilns near Lone Pine are a perfect example—two 30-foot-tall stone beehives from the 1800s, accessible via a one-mile dirt road. They’re not advertised, but they’re marked on historical maps and known to locals.

Search for “industrial heritage” near your route. Look for old mining towns, decommissioned military installations, or preserved agricultural infrastructure. These sites offer physical connection to history that polished museums smooth away.

The Natural Interruption

Every highway crosses ecological zones. Identify these transitions and plan stops around them. Driving I-70 through Utah? The stretch between Salina and Green River is famously devoid of services—over 100 miles of nothing—which means it’s also devoid of light pollution, making it perfect for stargazing. Time your drive for sunset, pull over at a scenic overlook, and wait for the Milky Way.

Hot springs are another natural stop that reward detours. Travertine Hot Springs near Bridgeport, California, is a short drive from Highway 395 and offers undeveloped soaking with mountain views. The Highway 395 guide notes it’s popular but worth sharing, especially during off-hours. These stops break up driving with immersive nature experiences that cost nothing but time.

The Rhythm of the Road: Timing Your Discoveries

Finding interesting stops is only half the equation. The other half is knowing when to take them. Over-schedule and you create anxiety. Under-plan and you miss opportunities. The solution is a flexible framework built around biological and environmental rhythms.

The 2-Hour Pulse Rule

Professional long-haul drivers follow a simple rule: stop every two hours, regardless of need. This isn’t about bathroom breaks—it’s about cognitive reset. A cross-country driver explains: “Drive less than 12 hours per day—7-8 hours is OK, but 4-5 hours is ideal if possible.” This slower pace creates space for discovery.

During each stop, consult your thematic map. What’s within 10 miles? A brewery that makes Ranch Dressing Soda (Indian Wells Brewing Company). A film museum celebrating cowboy movies (Lone Pine Film Museum). A volcanic obsidian dome (Mammoth Lakes). Choose based on energy and curiosity, not obligation.

The Golden Hours: Dawn and Dusk

The best stops often reveal themselves during golden hour lighting. A vista point that looks ordinary at noon becomes breathtaking at sunset. The Vista Point north of Mono Lake is explicitly recommended for its valley views at sunset. Plan your daily mileage so you’re near a scenic overlook during these times. If a stop is worth making, it’s worth making at the right time.

Conversely, urban exploration is best during midday when museums, cafes, and shops are open. A historic courthouse in Bridgeport, built in 1881, is best photographed in morning light but explored when the interior is accessible. Matching stop type to time of day optimizes both experience and photography.

Safety and Sanity: Venturing Off-Highway with Confidence

The fear that keeps people on the interstate is legitimate: What if we break down? What if we get lost? What if there’s no cell service? Proper preparation transforms these fears from prohibitions into manageable risks.

The 50-Mile Rule

Never venture more than 50 miles from the highway on a secondary road unless you’ve notified someone of your route and have a vehicle in good condition. Most interesting stops—charcoal kilns, soda fountains, scenic overlooks—are within this radius. The Bristlecone Forest is 45 minutes off Highway 395, which pushes the limit but remains feasible for a half-day excursion.

The Offline Map Insurance

Before leaving cell coverage, download offline maps of your target area. Google Maps allows this; Gaia GPS provides even better topographic detail for remote areas. A cross-country driver advocates this explicitly: “Be aware that there will be remote areas in the western states with no gas stations for 30-50 miles in any direction and plan accordingly.” The same applies to cell service.

The Grab-and-Go Bag

If you’re staying overnight in multiple locations, pack a small daypack with essentials: a change of clothes, toiletries, chargers, and snacks. As experienced travelers recommend, “Utilize a small ‘grab bag’ with a couple days’ of clothing & supplies so you’re not hauling your suitcases in at every stop.” This makes spontaneous overnight detours frictionless—you can stay near that hot spring or music festival without repacking the entire vehicle.

Living Examples: When Detours Define the Journey

The theory crystallizes in practice. These real-world stops from Highway 395 demonstrate how small detours create outsized memories.

The Soda Fountain Time Machine

In Randsburg, California—a mining town “that time forgot”—the general store still uses phosphates to make sodas from 1898 recipes. It’s 15 minutes off Highway 395 but feels like 120 years away. The lime soda isn’t just a drink; it’s a chemistry lesson in a glass, made with tartaric acid and sugar. This stop adds maybe 40 minutes to your drive but provides a story you’ll tell for years.

The Brewery of Absurdity

Indian Wells Brewing Company, 2 miles off Highway 395, makes 120+ sodas including Churro Soda and Ranch Dressing Soda. It’s a 15-minute detour that delivers pure novelty. The tasting room lets you sample the bizarre, and the staff’s stories about flavor development reveal a different kind of entrepreneurship—one driven by weirdness rather than optimization.

The Ghost Forest

The Ancient Bristlecone Forest requires a 45-minute detour and half a day to appreciate, but it rewards with trees over 4,000 years old. Walking among living organisms that predate the Roman Empire fundamentally alters your sense of time and travel. It’s not a quick stop—it’s a destination—but it’s precisely the kind of deep immersion that makes a long drive meaningful rather than a commute between destinations.

The Philosophy of the Detour: Embracing Imperfection

The ultimate skill in finding interesting stops isn’t technical—it’s attitudinal. You must accept that the best discoveries are inefficient, that a “wasted” hour at a disappointing museum is still better than an hour of white-line hypnosis, that arriving late with stories is superior to arriving on time with only mileage.

The Permission to Be Late

Build lateness into your schedule. If Google Maps says 8 hours, plan for 10. This buffer isn’t for traffic—it’s for possibility. When you see the hand-painted sign for “Hubcap Capital of the World,” you can stop without calculating the cost to your itinerary. The blink-and-you’ll-miss-it spot in Pearsonville takes 10 minutes to photograph but delivers a story about American roadside mythology. That’s a better use of time than arriving at your hotel 10 minutes earlier.

The Failure Premium

Not every stop will be worthwhile. That weird soda might be undrinkable. The museum might be closed. The hot spring might be crowded. This isn’t failure—it’s data. Each disappointment refines your intuition. You learn which sources to trust, which signs to ignore, which detours are worth the risk. Over time, you develop a sixth sense for interesting stops, but only by taking the risk of being wrong.

The Return on Curiosity

Calculate the ROI of stopping not in time saved but in memories gained. A year from now, you won’t remember the 20 minutes you lost at the soda fountain, but you’ll remember the taste of phosphate lime soda. You won’t recall the extra hour spent at the film museum, but you’ll remember learning that Tremors was shot in the Alabama Hills. These memories compound, creating a travel identity defined by discovery rather than destination.

The Road Is a Choose-Your-Own Adventure

The interstate system was designed to make America smaller, to shrink distance through speed. It succeeded, but in doing so it nearly erased the thousands of small places that give the country its texture. Finding interesting stops isn’t just about breaking up boredom—it’s about refusing to let the highway homogenize your experience.

Every exit you pass is a fork in your story. One path leads to efficient arrival, the other to unexpected memory. The skill isn’t in always choosing the interesting path—it’s in recognizing when you can afford to. Sometimes you need to make time. Sometimes you need to make memories. The wisdom is in knowing the difference.

Start small. On your next drive, take one exit that looks interesting but has no familiar chains. Follow one hand-painted sign. Ask one local where they eat. See what happens. The worst case is you lose 30 minutes. The best case is you gain a story that outlasts the destination. The highway will always be there, efficient and boring. The interesting stops won’t. Choose accordingly.